Info

All About Belgian Yeast

Before we hop straight into Belgian yeast, we first acknowledge the three major traditional brewing nations that started it all. We begin with England and its malt forward ales. These ales, along with many other variations, are the progenitors of most classic U.S. craft styles we know today such as IPA, Pale Ale, and Porter…

It seems like we can blame fungi and taxation for providing us the Belgian beer we know and love today.

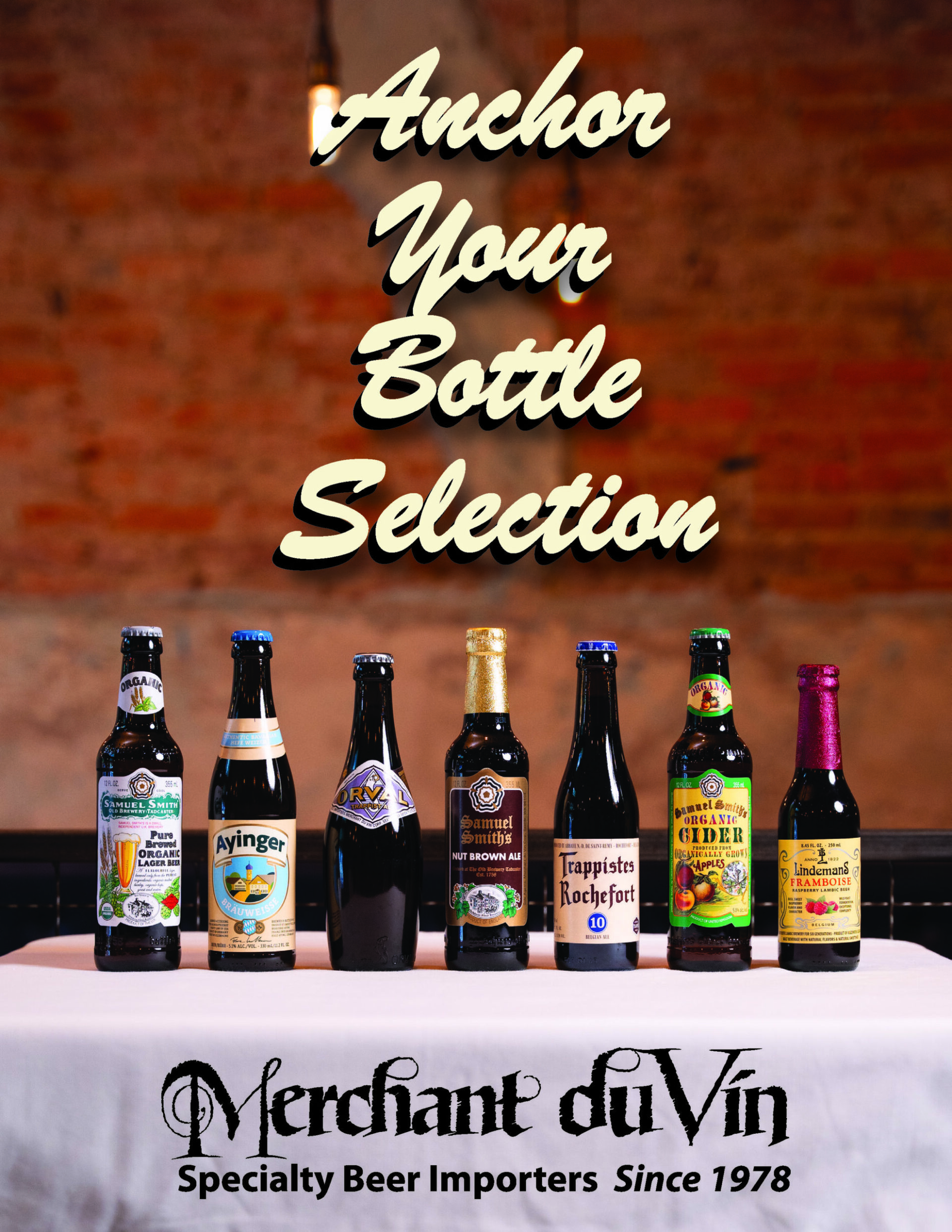

Before we hop straight into Belgian yeast, we first acknowledge the three major traditional brewing nations that started it all. We begin with England and its malt forward ales. These ales, along with many other variations, are the progenitors of most classic U.S. craft styles we know today such as IPA, Pale Ale, and Porter. Next there’s Germany, the lager capital of the world. Largely driven by traditional hops, and sharply restricted ingredients that put emphasis on technique, and not additives, these unique brews hold a special place in beer culture. Many Germans follow the Rheinheitsgebot purity law of 1516 and adhere to using only the 4 main ingredients in beer (water, malt, yeast, hops) and nothing else. Then there are those wild Belgians with spicy yeast and high ABV ales, which we’ll dive into.

Belgian yeast is what that really sets Flemish ales apart from many other varieties across Europe and the world. Distinct qualities in aroma, flavor, and overall stability set the stage for unique and tasteful beer creation using these fantastic fungi. These strains have been integral in carving out a special place for Belgian ales by adding floral, sweet, funky aromas and flavors without excessive hopping or additional flavor ingredients. This makes for an expanded flavor profile that is fairly inclusive to the region, and more specifically the yeast strains involved.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the scientific name for ale yeast. Thriving at warmer temperatures, they ferment quickly within one to two weeks of being added into the brew. Belgian variations have a substantial tolerance for alcohol content, making them perfect for brewing high octane blond ales, or Trappist ales like that of Westmalle and Rochefort. Historically, Belgian brewers were taxed on the size of their mash tun, which is the brewing vessel used to turn the starch in malted grains into sugar for the fermentation process. In order to avoid this excessive taxation, Belgian brewers found that by adding additional sugar into the wort, an infusion of malted barley and water, they could effectively ramp up the alcohol by volume tolerated by these special yeasts, adding additional depth and flavor without adding bulk to their brew. Ale yeasts lean heavy into fruity esters and spicy phenols, carrying with them aromas and flavors of pear, bananas, figs, cherries, cloves, and pepper. Heavy lifting for such a light load.

Wild or natural yeasts are the other variety of yeast that make a huge impact on beer, Belgian beer in particular. Wild yeasts are named aptly; they are bacteria inherent to the environment. These yeasts include the famous Brettanomyces bruxellensis, also informally known as Brett yeast, named after the country it was first isolated in: Britain. This special yeast is naturally abundant in the Zenne River Valley, home of the only ten lambic breweries in the world. Lindemans takes advantage of wild yeast, using it to brew Lambic ale between September and May, avoiding the hot summer months when other bacteria are rampant in the environment. Brettanomyces usually grows on fruit skins and is added, in Lindemans case, by exposing the wort to open air. Brett yeast creates a special funkiness many describe as a horse blanket or barnyard flavor alongside spices, fruits, and a bit of tartness. Special brews such as Orval Trappist ale introduce this strain for bottle-conditioning of their unique take on pale ale. Conversely, Brettanomyces in wine is extremely undesirable as it can cause a diminished fruit flavor intensity and a metallic aftertaste. Naturally occurring bacteria also play a role in brewing as they act very similar to yeast, except for converting sugar into acids instead of ethanol. Lactobacilli create an ‘umami’ or sweet and sour type effect as they break down sugar, while Acetobacters create a vinegary type of taste. Who knew science could add so much flavor?

Together these yeasts and bacteria have created a ‘culture’, no pun intended, that is undoubtedly unique and special to Belgian people and to the world. Today, we see the influence of these styles far and wide as appreciation for the craft has grown and experimentation into new realms of beer creation have taken hold. Thanks, taxes!

Santé!